Character Limit Exceeded

The Calculus of Tea in Crumbleton

He woke to the sound of hooves on tarmac.

Again.

It wasn't the gentle birdsong one might expect from a quiet suburban street in West Yorkshire, but the heavy, rhythmic clip clop that sounded like an old drummer practising a tedious, four legged tattoo on the pavement outside. Peter. A writer whose imagination, it seemed, had decided to stage a full scale occupation of his reality, rolled over, a groan catching in his throat. This wasn't just a metaphor for his creative process; it was a physical, insurance liability nightmare.

Outside, the familiar bright red float of the milkman, Mr. Davies, was parked askew. Mr. Davies, a man whose patience was as thin as the foil top on a bottle of semi skimmed, was locked in a heated debate with a centaur. The creature was a magnificent chestnut, all sleek muscle and powerful haunches, pawing the kerb with a nervous energy that threatened to crack the concrete. His long, black mane was intricately braided with fine silver thread, and his eyes, sharp and dark as freshly chipped flint, fixed on the hapless milkman.

“Look, mate, I don’t care if you’re a harbinger of post modern magical realism,” Mr. Davies was yelling, his voice tight. “You’ve dented my bonnet, and you’ve nicked a pint. That’s theft, that is.” The centaur, who Peter had arbitrarily named Chiron in a moment of classical pretension, tossed his head, causing the silver threads to jingle like tiny bells.

“It was necessary protein,” he rumbled, his voice a disconcerting blend of gravel and distant thunder. “The caloric requirement for maintaining this physique in a temperate climate is astronomical. And I didn't dent your ‘bonnet’; your vehicle, a crude, petrol guzzling affront to nature, simply failed to yield to a superior life form.” Peter watched the bizarre tableau from his sash window, his favourite earthenware mug warming his hands, the steam of his Earl Grey curling lazily around his knuckles.

He hadn’t meant to write a centaur.

It was always the way. He would tap away late into the night, fuelled by cheap tea and the quiet desperation of a man who wrote for a living, and the characters would simply... materialise. Last night’s frantic burst of creativity had been a gritty, noirish detective; all cigarette smoke, crumpled trench coat, and a distinctly cinematic limp from an unspecified old war. The day before, it had been a girl with iridescent wings who possessed a frustrating, self destructive refusal to take flight. They'd all manifested, fully formed, onto his quiet little street. They always came, demanding space, dialogue, and better plot points. With a resigned sigh, Peter pulled on his old, moth eaten navy coat. He shoved his feet into a pair of worn trainers, took one last gulp of tea, and stepped out onto the little gravel drive. Chiron’s magnificent head snapped toward him, his eyes immediately dropping to his own left foreleg, which he was resting at a slight, unnatural angle.

“You wrote me with a limp,” the centaur accused again, the accusation now directed at the creator himself. “A subtle, debilitating, and entirely unnecessary flaw. Why, Peter? I am a creature of myth, of speed, of the untamed forest. The limp suggests an unresolved trauma, a weakness!”

“It was meant to symbolise the burden of history, Chiron,” Peter said, stepping around Mr. Davies, who was busy taking photographs of the hoof prints for the insurance claim. “A way of grounding you in the narrative’s reality, preventing you from becoming a two dimensional plot device.” The centaur gave a mighty snort, tossing his head.

“Grounding me? It just makes it difficult to turn the corner at speed. I require speed.” He took a heavy, painful step. “Too late, then, isn’t it?” Peter saw the depth of the creature’s frustration. He had carelessly given a godlike being a very human, very annoying vulnerability. Peter nodded, surveying the slight hitch in the creature's powerful stride.

“Fair enough. My mistake, old boy.” As Chiron stomped away, muttering darkly about poor character development and the lack of decent hay, the postman, Gary, shuffled past. Gary, who used to deliver the mail with a jaunty whistle, now kept his eyes wide and vacant, the morning's letters clutched like a shield to his chest. He saw nothing, heard nothing, and that was the only way he survived.

The Detective's Missing Clue

Peter didn't head straight for the cafe. He spotted the detective, Merton, still loitering by the number 42 bus stop, his trench coat pulled tight around him despite the mild temperature. Merton was staring intently at a flattened crisp packet, muttering about 'clues' and the desperate need for a 'proper, black coffee.'

“Anything useful, Merton?” Peter asked, leaning against the cold metal of the bus shelter. Merton jumped, his pale eyes squinting through a cloud of fresh cigarette smoke.

“Peter. You shouldn’t sneak up on a man who’s dealing with The Void.”

“The Void?”

“The gaps, Peter. The missing bits,” Merton tapped the crisp packet dramatically. “This, for instance, is the brand Wotsits. But the packet is empty. The clue is not in the presence, but the absence.”

Peter sighed. “It’s just an empty crisp packet, Merton.”

“No, it’s a discarded subplot!” Merton jabbed a finger at Peter’s chest. “My case, the one you wrote for me, involves a missing woman. I was supposed to find a locket. A photograph. A reason for the rain! Instead, I find this town, which makes no damned sense. The case is a riddle wrapped in a chaos wrapped in a poorly edited manuscript.” Peter felt a familiar sting of guilt. Merton wasn't just investigating a crime; he was trying to find the coherence Peter had failed to provide. Peter had introduced a character defined by his need for order into a setting defined by narrative anarchy.

“I didn’t finish your chapter,” Peter admitted. Merton’s face was haggard. “We know. We all feel it. The loose ends. The dangling modifiers. I was written as a man with a purpose, Peter. Now I’m just a bloke with a cough and a limp, forever waiting for a bus that’s likely to be driven by a minotaur.” Peter promised to give him the locket soon—a concrete objective—and left the miserable detective to his philosophical crisis. He had his own literary fallout to deal with.

Fear of Freedom and the Mundane Knight

Inside, The Daily Grind was thankfully warm and smelled of burnt toast and strong espresso. The chaos seemed to be taking a coffee break. The girl with wings, Anya, sat nestled in the far corner, a quiet, almost forlorn figure sipping peppermint tea. Her silvery, feather covered wings shivered faintly in the morning light that streamed through the window, but she kept them deliberately folded and low, looking more like a slightly damp, nervous swan than a celestial being. She didn’t look up as Peter slid into the cheap plastic chair opposite her.

“You gave me a fear of heights,” she stated simply, not as a complaint, but a matter of inconvenient fact.

“I thought it would be interesting,” Peter said, beckoning the barista over. “A sort of psychological irony. A dilemma: the ability to escape, but the terror of taking it.” She finally raised a delicate eyebrow, a perfect, judging arch.

“It’s inconvenient. I was written to deliver something. A message of hope, or possibly a mythical object, I’m not entirely sure. But every time I get three feet above the chimney pots, I panic. I’m a metaphor for the fear of potential, Peter, and it’s terribly boring.”

“I apologise,” he murmured, stirring his own black tea. “I didn’t actually expect you to show up.” She gave a small, weary shrug, the movement making her wings twitch. “We all do eventually. The moment you name us, we’re anchored. And you named me Anya, which sounds like someone who drinks too much peppermint tea and worries about utility bills.” The small bell above the door gave a cheerful ting a ling. A knight, resplendent and utterly out of place in full, clanking plate armour, entered. This was Sir Peregrine, Peter’s brief attempt at a high fantasy subplot. The knight waited patiently in the queue, his armour giving a faint clink clink with every tiny movement, and ordered a plain croissant and an Americano. The barista, an unflappable young woman named Chloe, didn't blink. She knew the protocol: the knight always paid in gold florins, and she just factored the currency conversion into her tips. Peter looked at the knight, then back at Anya.

“I meant to write you two together, you know. A quest. A journey.”

“But you stopped,” Anya said flatly. “So now I’m having a mild panic attack about the pigeons on the roof, and he’s waiting for a toasted brioche. The potential for the epic is suffocating under the sheer weight of the mundane you surround us with.” Peter sighed. He was the problem. His inability to commit to a genre, his constant self sabotage, was manifesting as this surreal, exhausting reality.

The Library and the Guardian of Structure

He left the café, needing a moment of quiet reflection, and headed to the only place he felt marginally less responsible for: the local library.

As soon as he stepped through the oak doors, the silence was shattered. The tiny, grey haired librarian, Mrs. Hemlock, was frantically waving her arms at a volume of Romantic Poetry that was hovering indignantly near the ceiling, its pages flapping like a furious paper bird. It was one of Peter’s more whimsical, and therefore disruptive, creations; a sentient book that refused to be read.

“You’ve defiled Housman again!” Mrs. Hemlock shrieked. “A Shropshire Lad is supposed to be melancholy, not argumentative!” Peter ducked instinctively as the book swooped past him in a silent, indignant arc, nearly taking out a shelf of historical atlases. “You wrote this chaos, Peter!” Mrs. Hemlock hissed, clutching a well worn copy of Middlemarch to her chest, as if George Eliot’s structure might protect her. “I know,” he admitted miserably. “I’m trying to resolve the narrative.”

“Resolve it? You’ve added a grumpy troll to the Council Planning Department and now the bins aren't being collected! The faeries you wrote are unionising against the gnome population in the allotments! This isn't a story; it's a failed short story competition stretched to breaking point!” She slammed the copy of Middlemarch onto the desk, leaning in close. Her voice dropped to a conspiratorial, terrifying whisper.

“The town, Peter, the whole blessed place, it feeds on story. It needs logic. We’ve had writers like you before; the man who wrote the Great Flood of '98, the woman who conjured the perpetually singing paving slabs. But this town, Crumbleton, it protects itself. If you fail to finish, if you leave your characters in limbo, the town will not simply forget the chaos. It will absorb you into it.” Mrs. Hemlock slid a heavy, leather bound volume across the counter. It was blank, every page perfectly white. “This,” she said, “is the town’s Register of Continuity. The master plot. It is currently entirely empty because you keep overwriting reality. I want you to write a proper ending, a release for these poor souls, or I shall be forced to declare your narrative a Danger to Public Order.” He had no answer for her, so he simply offered a non committal shrug and retreated to the biography section, the silence there now entirely abandoned by the palpable pressure of untold stories.

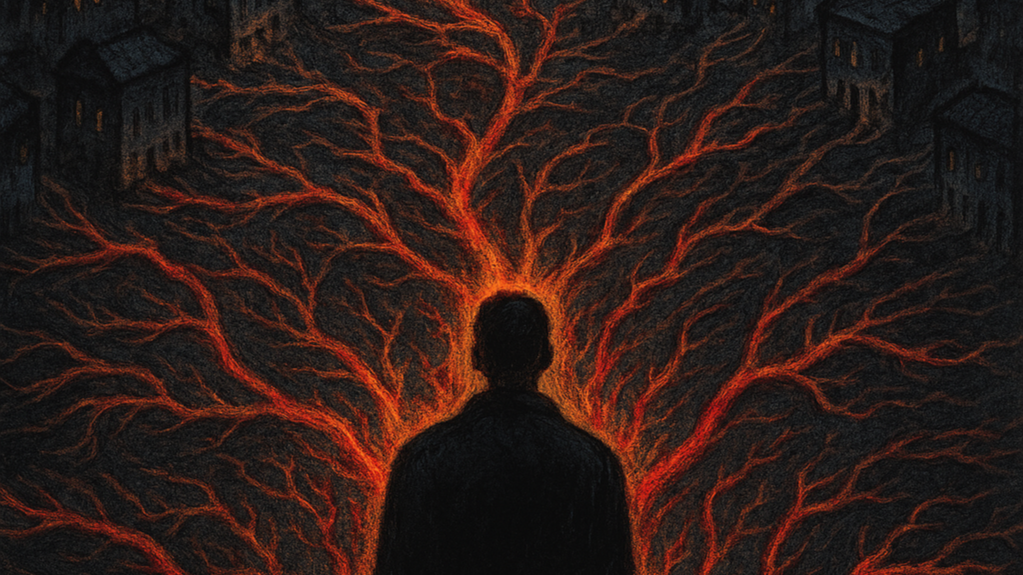

The Hour of Escalation

Peter returned home as the sun began to dip behind the terraced houses, casting long, unsettling shadows. The chaos, as Mrs. Hemlock had warned, was escalating. His neighbour, Mrs. Peterson, was standing on her doorstep, looking distraught.

“Peter! Your miniature dragons are nesting in my chimney again! They’re lovely little things, mind you, but they keep spitting tiny, perfect rings of smoke into my lounge!” He offered a weary apology, spotting a fat, mossy backed troll sat squarely in the middle of the street, casually blocking the evening traffic. A dozen frustrated commuters were honking their horns at the creature, who was simply reading the Daily Mail and occasionally scratching his fungal ear. This wasn't fun anymore. This was a nightmare of administration and guilt. He wasn't a god; he was a careless author who had forgotten the fundamental rule of writing: respect your reader, and respect your characters. He finally understood Merton's obsession with the missing locket, Anya’s fear of the sky, and Chiron’s limp. These weren't quirks; they were burdens, imperfections he’d slapped onto their existence without considering the consequence. He had used living, breathing beings as scaffolding for his own poor character studies. He looked up. The sky above Crumbleton was a strange, bruised purple. He saw Anya circling, lower than ever, her wings fluttering desperately as she fought the urge to simply drop. He saw Chiron in the distance, pausing to favour his bad leg before moving on. The entire town was groaning under the weight of his irresponsibility. He needed to save them. He needed to write a final chapter so perfectly, so cleanly, that it would release them all back into the quiet oblivion from which they came.

The Final Sentences

That night, Peter sat at his worn pine desk in his tiny home office. The cheap desk lamp cast a small, intense pool of yellow light across the stark, blank sheet of paper before him. He stared at the emptiness, his mind a churning mess of centaur limps, nervous postmen, and inconvenient wings. He thought about Mrs. Hemlock’s threat: the town was hungry, and if he didn't finish the story, he would become the next, most tedious character of all The Writer Who Couldn't Finish. His pen hovered, the nib trembling slightly just above the page. He couldn't write an epic conclusion. He couldn't invent a magical portal or a climactic battle. He was out of energy, out of plot. He had to write the opposite of a story. He had to write a cancellation. He pressed the pen down, the ink bleeding slightly into the fibres of the cheap paper. He wrote the three most potent, terrifying words a writer could commit to the page: A man who forgets what he’s written. He paused, the sentence a desperate spell. It was a plea for personal oblivion, a release from the crushing burden of creation. Then, with a firmer hand, he wrote the second line, addressing the suffering of the town: A town that forgets what it’s seen. He hesitated for a long moment, listening to the silence of the suburban street, a silence he knew to be full of unseen, impossible life. Could he really erase the life he had brought forth? Could he sacrifice his own purpose for their peace? Then, in bold, final strokes, he wrote the sentence that would sever the anchor, that would destroy the wellspring of the chaos, the one true way to save them all: A writer who stops writing. He put the pen down, letting the full, incredible weight of the last sentence settle over him like a heavy, final blanket. The ink of the three sentences seemed to pulse faintly in the lamplight.

Outside, the wind began to stir, but it was a cold, clean wind, not the chaotic gust of his imagination. He heard a sound that was suddenly distant, muffled, as though heard through thick glass. The centaur limped past his window, but this time the hoof beats seemed softer, dissolving into the silence. The detective was still out there, lurking in the shadows of the sycamore tree, lighting another thin, cheap cigarette, but the smoke now rose straight and steady, without a hint of narrative mystery. And high above, just barely visible, the girl with wings circled the cul de sac. She was flying higher than before. She was no longer battling a fear of the heights; she was simply rising. Peter watched until she became a vanishing silver pinprick against the vast, dark expanse of the night sky. The knight, the troll, the indignant book, they were all simply... gone, their reality cancelled by his final, decisive act of self erasure. He was just Peter now, an ordinary man in an ordinary coat, sitting at a quiet desk. He looked at the three sentences, then turned toward the window, watching the last vestiges of his imagination fade. The wind died down entirely. The street was still.

Then, with a click that sounded deafening in the silence, he turned off the lamp.

Some people move through the world making noise. Thirteen-year-old Leo has learnt to be still. But when an old illustrated book vanishes from the bookshelf, Leo discovers something extraordinary living in the walls of the Victorian house: the Snibbit, a small magical creature that collects beautiful things and understands that silence can be full of meaning. Through carefully preserved fragments from the past, the Snibbit teaches Leo how to navigate a world that isn't built for quiet people.