The Silence Between Us

The sky was the colour of wet ashes. It had been for as long as I could remember. No sun, just a weak, flat light that stripped the world of contrast and shadow. This perpetual twilight was not peaceful; it was a constant, grinding pressure on the eyes and the mind, a visual equivalent of static that ensured no view, no matter how vast, could ever truly be beautiful. It leached the soul from the ruins we inhabited.

The notebook in my bag was heavy. It was a stubborn protest I never used. Words felt like lies. In this new world, language had collapsed. Why describe a grey sky when all skies were grey? Why articulate hunger when every breath was an articulation of it? The notebook, a gift from a time before the Ash, was a relic of useless complexity. It was a burden, but I carried it, a small, irrational ballast against the absolute pragmatism of our existence.

Grit walked ahead of me, low to the ground, his body a study in functional economy. He was large for a dog—shepherd stock mixed with something leaner, maybe ridgeback—his fur the same colour as the wet ashes that filled the sky, a mottled grey-brown that made him nearly invisible against the landscape. We'd found each other in the first winter after the Ash, two desperate creatures who understood that survival meant partnership. He'd chosen me as much as I'd chosen him, a mutual contract written in hunger and necessity.

Scent of metal and sick, Grit's thought struck me. It wasn't sound; it was a pure, cold idea dropped directly into my mind, a mental punch that bypassed the ear and registered instantly in the hindbrain. We didn't talk aloud anymore, not unless absolutely necessary. Sound carried too far. And Grit's mind-voice—the way he projected his thoughts—was an instrument of total efficiency. To the right. Low wall. Moving slow.

He didn't break stride. He was the efficient engine of our survival—all instinct and muscle honed by years of walking the edge. His movements were minimalist: no wasted energy in his gait, his eyes constantly scanning the near distance and the periphery. Grit was the pure equation of survival: input threat, output solution.

I tightened my coat collar. The thin, abrasive wind carried nothing but the dust of dead things. We moved toward the low, busted concrete wall. It was a common sight, a boundary for some long-dead factory or housing unit, now just a crumbled line on the landscape.

The man was there. Old, bundled in sodden, grey blankets that matched the environment perfectly, collapsed against the cold stone. He was dying. It was a slow, quiet death, the kind we saw daily: a gradual fading as the body simply ran out of fuel and will, assisted by the low-grade, ever-present illnesses that preyed on the weak.

Do not stop, Grit commanded, his posture turning into a taut wire. The thought was a sudden spike of anxiety and control. Waste of time. Waste of risk. He has nothing. His light is out. Walk away.

Grit's philosophy was absolute. Survival meant zero-sum calculation. Any expenditure of energy, water, or attention on the non-viable was a direct subtraction from our own slender chances. He saw death not with cruelty, but with the cold detachment of a mathematician recognizing an inevitable result. The man's 'light is out': the ultimate verdict of our time. It meant the flicker of internal fire, the metabolic rate, the last reserves of life—all gone.

The man coughed. A wet, tearing sound, like wet cloth ripping. It was a sound of finality, one that cut through Grit's cold logic.

"Wait," I thought back, the word feeling clumsy and soft against the razor-edge of Grit's logic. It was a purely emotional response, a flicker of the old world's obsolete moral code. We should help. An utterly indefensible position, yet the thought persisted.

The man's eyes rolled toward me. Grey, filmed over with cataracts and the general detritus of exhaustion. They were the eyes of something fished up from the deep and left to dry.

"Beyond," he rasped, his voice a dried whisper of sound that made Grit momentarily flinch at the auditory exposure. "The flats. The salt… there is a green place."

The words were a seismic shock in the silent, grey world. Green. A colour of legend, a concept of myth. We only knew the muted, sickly yellows and the omnipresent, suffocating grey. Green meant life, water, growth, a world that was not dying.

I reached for the canteen. The small one. It held the last of our sealed water, enough for one more day—the last buffer against certain death on the open road. It was the most valuable thing we possessed, a physical embodiment of our immediate future.

No. Every drop is tomorrow. Do not break the seal for him. Grit's thought was a wall of pure opposition. I could feel his frustration, his internal calculation screaming at my illogical impulse.

I ignored him. My body was moving before my mind had fully committed. I knelt down, the cold of the highway seeping into my knees, and tipped the canteen, letting a small, stale stream wet the man's lips. The water was flat, chemically purified, and tasted faintly of the metal flask, but it was wet. It was life.

He swallowed once. His eyes found mine, suddenly clear, the film receding for a single, incandescent moment. There was gratitude there, not for the sip of water, but for the acknowledgment.

"Green," he whispered again, the word this time holding the tone of an absolute truth, a personal revelation he had carried to the end. And then his hand fell, settling on the ash-dusted concrete. His light was out. The small, stolen drop of water had bought him a final moment of lucidity, nothing more. The cost, however, was incalculable.

You feed ghosts, Grit finally sent, the thought heavy and final, a judgement delivered with weary certainty. We move. Quickly. He dies. We live. That is the only maths left.

He didn't wait for a response, already turning to walk parallel to the wall, accelerating our pace. The brief, foolish detour was over.

We turned from the low wall. I didn't look back. There was nothing to see but a sodden grey bundle against a cracked grey wall under a sky of wet ashes. But the word, green, was a small, foolish ember I carried with me, an illogical, dangerous hope struck from the cold flint of a dying man's final breath. It was a contamination in the purified logic of survival, an entry point for a yearning that could get us killed. Yet, walking away, back into the endless, colourless expanse, the thought of a "green place" was the only shadow in the perpetual flat light—a promise of contrast, a hint of something more than just tomorrow. It was a destination, a delusion, or perhaps the only truth that mattered. The burden in my bag was no longer the heavy, unused notebook; it was this single, vibrant word.

The highway stretched ahead, a ribbon of decay. Every step was a commitment to the "maths" Grit lived by. Conserve. Move. Watch. I knew he was angry. Not the hot, explosive anger of a time before, but a cold, measured fury at my lapse in discipline. To him, I had spent the most precious commodity—water—and the second most precious—time—on a piece of waste ground. Worse, I had done it for an abstraction: kindness.

The unspoken tension between us was a third walker on the road. It was a necessary friction; my occasional, reckless humanity checked by his brutal, focused pragmatism. That was how we had survived this long. He was the guardrail; I was the one who occasionally leaned too far over the edge to look at the view—or the dying.

I could still feel the faint wetness on my palm where the canteen had been. The man's final clarity was the payment. That moment of true sight, unfilmed by suffering, was a testament that even here, beneath the crushing weight of the Ash, the idea of life persisted. That "green place" was now an unrequested, and possibly fatal, deviation from our established route south toward the rumored Coastal Scraps. The Coastal Scraps were a known risk, a known quantity of resources and raiders. The flats, the salt… that was pure unknown. And in the Ash, the unknown was usually fatal.

I waited for Grit to project another thought, a final, cutting remark to end the episode. But none came. He simply walked, his focus already reset, his mind tracking the subtle movements of the air, the distant, almost inaudible scrape of something metal on the cracked road ahead. We were back to the silence, back to the efficiency. But the silence was different now. It had a secret tucked inside it—a whisper of green against the ash.

Two days later, the landscape had not offered a single change of scenery, only an intensification of the oppressive grey. My gut was tight, a persistent knot of hunger that was no longer a sharp pain but a dull, chronic ache. The memory of the single sip of water given to the dying man was a small, stinging regret, a foolish expense. We came around a broken concrete wall, an anonymous shield against the wind. A woman was there, thin as wire, sitting on a rusted shopping trolley —one of the ubiquitous, broken chariots of the apocalypse. A silent child, bundled in threadbare, grey fabric, was pressed against her chest, its face invisible. They were an unmoving sculpture of want, perfectly framed by the ruin.

My hand went, unbidden, to the canvas bag slung across my back. Inside was the spare tin of beans. It was our luxury, our insurance, meant for a crisis or a final push. It represented almost a day's worth of calorie density.

No, Grit hit my mind like a block of ice. The thought was immediate, cold, and absolute. Not for her. Her time is done. She's just hunger now. To Grit, people who had reached this level of emaciation were already past the point of viable return; they were resource sinks, dangerous because they had nothing left to lose. He saw them as predators in their final stage.

I knelt. The movement felt heavy, slow, a violation of the imperative to move swiftly and silently.

Fool. Stop this, Grit's presence flared, a hot, bright spike of warning. He was low to the ground, his eyes darting, searching for the invisible threats he felt surrounding the woman. You take the risk for nothing. She will try to take the bag. She has to. His logic was flawless: survival dictated that she must attempt to seize what little I had left. Her maternal instinct, the desperate need to feed the silent child, would force her hand.

Ignoring him, I reached into the bag, pulled out the tin of beans, and slid it across the dirt. It was a calculated risk, a desperate payment to the ghost of my conscience. It clinked against the cart's rusted wheel, a loud, metallic sound that seemed to shatter the pervasive silence. The woman didn't move to grab it, or the bag, or me. She simply watched.

A tax you pay on your own flesh, Grit sent, his mind-voice quieter now, laced with disappointment rather than fury. She will only remember where you keep the rest. Why do you feed ghosts? His question was the central, unanswerable one of our journey. Why cling to the useless virtue of a dead world?

I stood up, my knees stiff. She looked at the tin, then at me. Her eyes were sunken but held a startling moment of recognition, a brief flash of the human being beneath the desperation. A single tear cut a clean, dark line through the dirt on her cheek.

"Thank you," she rasped, the word thin and dry.

I gave her a quick, hard nod. I didn't wait to see her open the tin. I kept walking, my steps even, steady. The truth was, my actions were indefensible by the "maths" that kept us alive. My impulse was a foreign body, a disease in the logic of survival. But the gesture was a momentary lifeline to my old self, a clumsy attempt to prove I was still a human being, not just a mechanism of survival. My actions were the sound of an old, broken language I couldn't forget how to speak.

The cold was the deep kind that settled in the marrow, the chill that no amount of grey wool could truly defeat. We had been walking for twelve hours, and every step was a separate negotiation with exhaustion. We needed rest—a protected space, out of the wind, where we could light a small, carefully shielded flame to warm our ration of gruel.

We saw it as the sky turned a bruised purple: a small, sturdy-looking concrete block building with a makeshift door crafted from a scavenged sheet of metal. It was perfectly placed, a small, dark cube against the expanse of the dying light. A promise of a few hours of safety.

I sped up, my focus locked on the doorway.

Oil. Stench of decay and metal, Grit's thought came, a low, guttural vibration that dragged against my rising hope. He slowed, his body language turning instantly cautious. We pass. This place has been opened and closed too many times. It smells of waiting.

Grit's senses were fine-tuned instruments for reading the history of a place. The "oil" wasn't simply residual; it was the scent of freshly worked metal, suggesting recent occupation or, worse, a recent setting of something. The stench of decay was not the general background smell of the Ash, but a specific, concentrated odor—a bait.

I ignored him, my desperation for warmth overpowering my caution. I moved toward the door, planting my boot firmly on the swept concrete patch outside the doorway, eager to claim the shelter.

The air went dead. The silence around me—which had always been an absence of sound—suddenly became a presence, thick and warning. I heard a small, tight click in the bone of my heel. It was an almost imperceptible sound, but in the silence, it was deafening.

NOW! Grit's telepathy was a physical shockwave. He didn't just project the word; he hammered it into my mind. He sprinted at me with startling speed. JUMP, FOOL!

The concrete slab I had stepped on pivoted slightly. A wire, thin as thread and almost invisible, pulled taut across the doorway a foot off the ground. It was a wickedly simple tripwire, the pin of an explosive charge released beneath the slab, or perhaps a heavy, falling weight rigged above the door. It sliced across the back of my left calf. The pain was a searing line of fire, immediate and blinding. I stumbled, the impulse to find balance lost as the shock raced up my leg. I fell toward the trap.

Grit slammed into my shoulder, not a push but a deliberate, low tackle that spun me out and away from the doorway into the deeper ash, sacrificing his own momentum to save me. We landed hard, the impact jarring the breath from my lungs.

See the cost of your hope? Grit's voice was low, furious, delivered this time through his teeth, a whisper of sound that was a pure outlet for his anger. The hunger in that house is not satisfied by beans. It wants blood.

My hand came away from my calf wet and slick. The wound was shallow, a razor-thin slice where the wire had caught me, but it bled freely, a dark, pulsing line staining my trousers. The sight of the blood, so red against the grey, was a violent shock of colour in this world of ash.

"Let's move," I whispered, the words grating on my throat, already scrambling to my feet. The pain was a secondary concern; the primary was the danger we had just confirmed. Whoever set the trap knew what they were doing and was likely close enough to investigate the noise.

The lesson is paid for, Grit stated, his voice a cold mirror of my own failure, devoid of comfort or pity. We do not ignore the way the air lies. He did not ask if I was hurt; he simply observed the fact. My injury was now another variable in the survival maths.

We turned and moved away, silently and quickly, putting distance between ourselves and the deadly promise of rest. The cold seeped back in immediately, sharper now, intensified by the bleeding. I left a small, dark stain spreading on the grey ground where I fell, another offering to the hungry, waiting land. The tin of beans was a tax I paid willingly; my blood was the price of ignoring Grit's cold, pure logic.

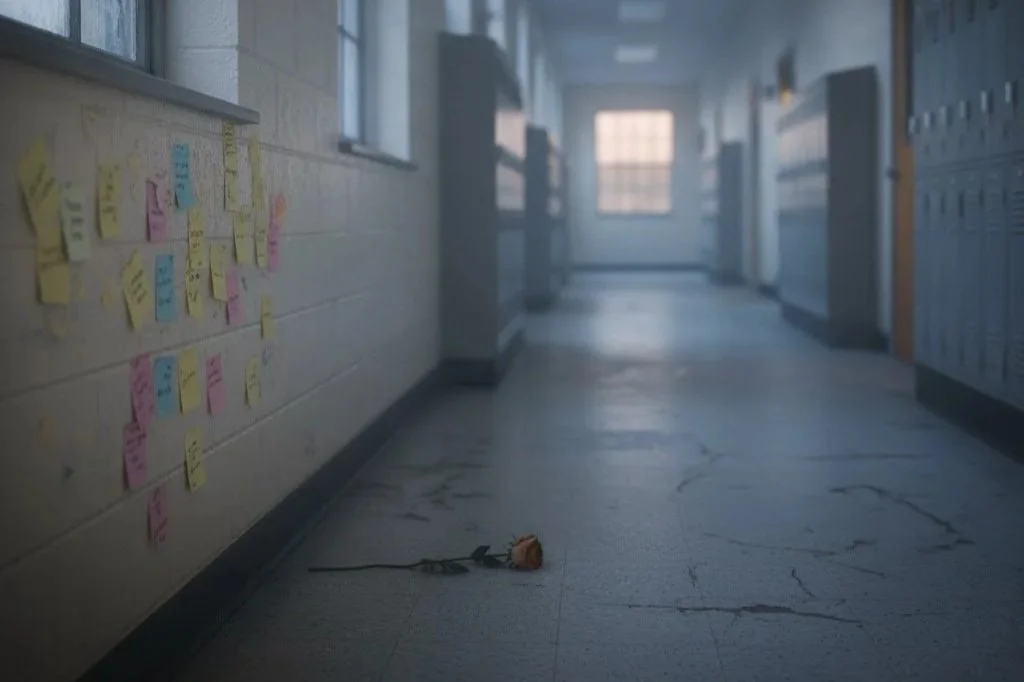

The library stood like a cracked ribcage against the bruised grey sky, a ruin of concrete and glass shards. It was one of the few buildings still partially standing, spared by whatever localized disaster had felled its neighbours. Its windows were empty sockets, its roof a jagged line against the flat horizon. I stepped inside the broken main door, crunching over layers of dust and fallen plaster. The air that met me was heavy, still, and thick with the unmistakable smell of mildew and paper rot, a ghostly scent of intellectual decay.

It is a grave of trees, Grit sent, his mind-voice restless, a low thrum of discomfort. He stood just inside the main archway, remaining firmly in the light, his eyes scanning the gloom with suspicion. No food. No water. We leave it. To him, the building was a thermodynamic anomaly: cold, dark, and offering no calorific return. It was worse than useless; it was a distraction. He didn't trust stillness, especially not a stillness that smelled of old, forgotten things.

I ignored his command and moved deeper inside. I felt an inexplicable pull toward the silence of the shelves, toward the decaying remnants of accumulated knowledge. It was a compulsion I couldn't articulate, a hunger distinct from the knot in my stomach. The main hall was a jumble of fallen shelves, the books spilled out like the entrails of a gutted beast, their pages fused by moisture and time into solid, unreadable blocks.

I climbed the ruined stairs. The treads creaked under my weight, the noise echoing unnervingly in the vast, hollow space. Grit did not follow. He was anchored to the ground floor, a sentry of pure caution.

On the second floor, the damage was less severe. I navigated a maze of tipped-over chairs and filing cabinets until my eye caught a flicker of colour—not the dull yellows or relentless greys, but a faint, faded blue. I found a book, a small, battered collection of poems, wedged against a broken window frame, somehow preserved from the moisture. I sat down on a tipped-over metal filing cabinet, its drawers half-open like slack jaws.

I opened the book to the ripped-out page that had served as the seal, and began to read aloud, a low, hesitant murmur that felt alien and strange in the monumental silence: "...And when the long day goes, the shadow of the rose remains, though petals drop and winter knows no shame..."

Stop the sound, Grit ordered, the irritation sharp, a sudden, forceful spike in my mind. It is wasted air. What use is the noise? It is the language of the soft. It will kill us. His logic was ironclad: sound attracts danger; poetry provides no sustenance; the time spent is time not spent moving toward a sustainable future. The concepts in the book were antithetical to survival. They spoke of beauty, permanence, and memory—all things that had been wiped clean from the slate of the Ash.

I kept reading, letting the peculiar rhythm and the strange, evocative words wash over the ragged edges of my consciousness. I didn't understand the poem; the language was highly stylized, discussing emotions and experiences that were now theoretical concepts—roses, shame, winter that knows things. But the rhythm, the deliberate pattern of the syllables, felt like the shape of something I was supposed to remember, a lost syntax for the soul.

"It is a map," I thought back to him, the justification sounding flimsy even to my own mind.

It is a lie. The map is the path beneath our feet. The only language that matters is the one that says: live. This sound you make says: stay. Grit's counter-argument was absolute. The map was the immediate landscape; the language was the unspoken code of vigilance and movement. Anything else was a fatal indulgence.

I reached out and ripped the page out, tearing it carefully at the seam of the spine. It was a conscious act of theft, preserving a sliver of the building's essence. I folded it small, feeling the dry, brittle paper under my thumb, and tucked it securely into the inner pouch of my coat, next to the small, empty canteen. I stood up, leaving the rest of the book behind, its small weight now transferred to me.

The interlude was over. The cold, practical reality of Grit's presence was a powerful counterweight to the spectral draw of the library. I had wasted time for dust, for a handful of fragile, useless words. But as I rejoined him and we stepped back into the ash-dusted silence, the words—the shadow of the rose—felt like a small, fragile shield against the cold.

We began walking again, the library sinking behind us into the perpetual twilight. My small act of dissent had not been for the woman with the beans, nor for the dying man with the water; it was for the part of myself that refused to be defined solely by the "maths" of survival. The rose had died, yes, but its shadow—the memory of its beauty, the persistence of its shape—was what I was truly fighting to save. That shadow, those useless words, contained a promise that when the long day goes, not everything is lost.

Grit did not comment further on the time I'd taken. The unspoken tension simply deepened. He was the anchor; I was the small, fragile kite, perpetually testing the tautness of the line. The small, folded page in my coat was a subversive element, a tiny packet of rebellion. It was a secret contract with the dying man: the promise of green and the shadow of the rose—two completely impossible things that now defined a future more compelling than the simple, brutal guarantee of another grey sunrise. The physical wound on my calf ached, a reminder of the cost of ignoring caution; the words on the page were an equally dangerous, invisible wound to my discipline, a constant temptation to look beyond the survival of the body and toward the preservation of the spirit. And in this ash-world, one was as fatal as the other.

We reached the salt flats. The transition from the fractured concrete of the highway was absolute. Suddenly, the ground was a blinding, endless sheet of white, a vast, flat expanse of crystallized sodium that reflected the weak grey sky with searing intensity. It felt like walking on the face of the moon, a world stripped down to two colours: white ground and grey air. The silence here was different—not the heavy, dust-filled stillness of the ruins, but a brittle, echoing silence that magnified the sound of our boots crunching on the salt crust. It was beautiful in a terrible, minimalist way, a landscape that promised neither life nor shelter. The wind here was dry, carrying only the taste of iron and salt.

We had been crossing the flats for three days, the horizon remaining stubbornly unchanged. The exposure was relentless. On the third afternoon, we found them. A cluster of tents, patched with grey tarps and stabilised with stones, nestled near a dead-standing, rusted oil pump. It was a landmark, a point of elevation, and a place to avoid, but we were too close before we saw the movement. They were militant, wrapped in scavenged armour plates and heavy, dull fabrics, their faces obscured by grime and suspicion. They moved with a practiced, predatory caution, their dull eyes constantly scanning, their rifles held too tightly. They were the human equivalent of the landscape: harsh, practical, and utterly merciless.

They stopped us with hard voices that cracked the salt-silence. They weren't interested in our pack, which held only meagre rations and the precious, near-empty canteen. Their eyes went straight to the canvas bag I carried—the one that held the spare tin—but then they settled with a focused, animalistic hunger on Grit.

The air on the salt flats cracked with a tension colder than the metallic wind. The woman, whose face was bisected by a ragged, silver-white scar across her cheek, stepped forward, a monument of necessity and hardness. Her hand rested on the stock of her rifle, a casual threat that was anything but casual. Her voice was flat and non-negotiable. "The boy can stay. We have work. We have walls. We can use a pair of legs that aren't shaking." Her words were an offer of grim, indentured survival. "But the dog is meat. We eat tonight."

Do not fight, Grit finally sent, the thought settling in my mind with a terrible, resonant finality. His voice, when it came, was not the usual razor-edge of logic or frustration. It was steady, impossibly calm, a sacrifice rooted in pure, cold logic. This is maths. They take me. You live. This is the last loyalty. He had calculated his final worth: maximum benefit was achieved through his death, not his defense. His life, he knew, was justified only by its utility to mine. If his death secured my future, it was the perfect, final iteration of his purpose.

I looked at the scar-faced woman, whose eyes were waiting for my choice, not with malice, but with a terrifying, professional indifference. She had made the trade countless times. I looked down at Grit, whose gaze was fixed on mine, his eyes clear and absolute. He was asking me to choose his logic over my own humanity, his perfect, cruel maths over the clumsy, obsolete language of emotion. He was demanding that I let him become the ghost I had been feeding.

"The dog is useful," I said, my voice barely scratching the dry air. I grasped for a language she might understand—the language of utility. "He scents trouble before we see it. He saved me from a trap two days ago. We've got nothing else to offer."

The woman's lip curled slightly, but her eyes didn't soften. "He saved you because you’re soft, boy. A good scout doesn't need a dog. He needs to listen. You brought a tin of beans to an open sore. You're bleeding out virtue." She shifted her stance, tilting the rifle barrel slightly. "That’s what he protects—your weakness. We don't need your weakness. We need the calories."

"He's not a pet," I insisted, the desperation catching in my throat.

She took a single step closer. "Everything is a resource. Everything is a tool. You choose your tool, boy. The dog, or the walls. They are mutually exclusive. We are not negotiating the life of the meat."

Fool, Grit sent, his mind-voice rising with a spike of sharp impatience, his control wavering for the first time. You will both die for a feeling that has no name. Let them take me. It is fast. You carry the truth forward. He was urging me to remember the green place, the shadow of the rose—the abstract things I claimed to value.

"The truth is here," I thought back, placing my hand flat on Grit’s head, feeling the coarse hair and the familiar, solid ridge of his skull. The truth wasn't a poem or a colour; it was the companionship that had kept me sane.

I met the woman's gaze, my throat dry, the cold salt air stinging my eyes. The decision was a pure, irrational defiance. I chose the worthless thing, the emotional anchor, the language of the soft.

"No," I whispered. My throat was dry, the single word a defiance against the entire, brutal logic of our world. "Neither of us."

The decision was a blink of cold clarity. I didn't hesitate. I lunged, not at the militants, but at Grit, shoving him hard to the side. The movement broke the tableau, shattering the brittle moment of negotiation and silence. It was a declaration of war against maths.

A rifle shot rang out, muffled by the distance and the salt haze, the sound flat and disappointing. Grit yelped. Not a command, not a thought, but a sound of pure pain, animal and raw, immediately cut short.

I didn't look back to see who fired. I grabbed his harness, a salvaged strip of leather, and pulled him low, away from the cluster of tents, plunging toward the featureless expanse of the flats. He ran, driven by adrenaline, staggering on three legs. The lead weight in my legs was gone, replaced by a terrible, cold fire that lent me impossible speed. Every breath was a shard of salt.

We ran until the militant group was just dark specks behind the salt haze, their shouting fading into the wind's abrasive whisper. Then Grit's front legs buckled. He collapsed, heavy and silent, scattering the white powder into a sudden, ephemeral cloud. I dropped beside him, shielding his body with my own until the shouting faded entirely into the wind, replaced only by the dry, rasping sound of our own desperate breathing. The wound was on his shoulder, a dark, spreading stain blooming across the white salt. The silence was back, but now it was a shared, terrified vigil. I had saved his life, but I had paid a price I couldn't yet calculate.

We collapsed at the edge of the flats. The terrain shifted beneath my feet without warning or transition. One moment, it was the blinding, cracked white of the salt, the next, it was cracked mud, then abruptly, impossibly, to moss and green shoots. It was a geological, biological miracle, an oasis stumbled upon after days of lunar desolation. The salt flats gave way to a sudden, gentle valley. The air here was quiet, utterly still, and overwhelmingly scented with life. It smelled of fresh water and growing things, a profound, shocking contrast to the metallic, dusty stench of the Ash. It was the "green place" the dying man had whispered of. It was empty.

I carried Grit the last fifty yards. He was a dead weight, heavy and limp in my arms, his body slack with shock and blood loss. The sheer weight of him was a devastating physical confirmation of the damage, but his mind was still a flicker in mine, a weak, sputtering ember that refused to be extinguished completely. The adrenaline that had propelled me across the flats had faded, leaving behind an exhaustion so deep it felt structural.

I laid him down carefully in the new, resilient grass. The soft cushion of green was a small comfort, a gentler bed than the salt or the concrete. His breath was shallow, rattling, catching in his chest with every painful inhalation. The wound in his shoulder was dark and thick, the blood no longer flowing freely but coagulated into a terrible, solid mass. It was deep, closer to the vital organs than I cared to admit. I knew it was over. The maths Grit lived by—the absolute necessity of vitality and function—had been violated by a single, brutal bullet. His efficient engine was broken.

I lay beside him, the overwhelming, humid scent of the moss and the fresh dirt washing away the ingrained perfume of dust and decay that had clung to me for years. It was a sensory reset, a reminder of the world that had been lost, now found again in miniature. For a long, silent time, I simply rested my cheek against the damp earth, drawing deep, shaky breaths of the clean, green air.

This is not the end, Grit sent, his final thought fading in and out like a weak radio signal, the connection between our minds fraying and snapping. It was a struggle for him to push the thought across the widening gap. It is the pause. Now you walk. His final instruction was a command for continuity, a demand that I not halt my survival to mourn his. He was giving me my marching orders into the green place, ensuring his last act was an act of purpose.

I didn't answer. There was no point; the connection was already too weak for dialogue, only for broadcast. I sat up, my limbs shaking with reaction and the cold of the slowing blood. I didn't cry. There was no sound for this kind of loss, no measure for the vacuum that was about to open in my mind. Crying was a luxury, a waste of energy and fluid. Grit would have hated it.

I took the shard of a broken shovel from my pack, a piece of scavenged metal that had served as a crude hand-axe and trowel, and began to dig the hole. It was an act of terrible intimacy. The earth here was soft, giving, but the labour was still immense. It took hours. Every shovelful was an extension of the time I refused to let him go, a protest against the finality of the Ash-world's maths. The sun, finally able to punch a weak, diffused light through the perpetual grey, was beginning its slow arc toward the unseen horizon when I finished.

I wrapped him in the last of the blankets, the heavy, grey wool a final, warm shroud against the cold earth. As I did so, I reached into my inner pouch and withdrew the small, dry-folded poem, the piece of useless protest ripped from the library. I unfolded the page just enough to read the words for the last time—"...the shadow of the rose remains..."—and then I placed it gently beside his head. It was a symbolic gesture, a concession to the part of me he had always protected: the part that valued the intangible. He had died to preserve my journey to the green place; the poem was a symbol of the beauty and language I was carrying there.

When the grave was filled, the mound of fresh earth, a dark, profound scar on the new green grass, I sat beside it. The world was quiet, waiting for my next move. I reached for the heavy notebook I had carried, the stubborn protest I never used. I opened it to the first, blank page.

I didn't write words. Words were lies, Grit had taught me that. They dressed up truth in unnecessary complexity. I wrote what was true. I drew him. It was a crude, simple line drawing, executed with the stub of a pencil: a faithful representation of Grit, low to the ground, head up, watchful. It was not a memory but a a lament, or a record of loss. It was a command. The image of him—his posture of perpetual vigilance and efficiency—was the only map and the only language I needed to survive the green place. He was the shadow I would carry forward, the essence of the maths that kept me alive, now internalised and absolute. I closed the notebook, a weight heavier and more purposeful now than it had ever been. The pause was over. Now, I walked.

The ash fell still, settling on the soft, damp moss of the valley floor. But now, it dusted the shoulders of trees, not just the cracked grey concrete of the old world. The green here was a deep, uncompromising emerald, the air thick with the scent of pine and damp earth. It was a place of terrifying paradox: lush life sustained under a sky of perpetual ash.

The notebook, aged and warped by weather and the salty air of the flats, lay half-buried near the burial mound, near the place where the moss began its ascent up the valley wall.

A new child, perhaps ten years old, found it. She was wary, alone, a small figure bundled in grey rags that seemed to absorb all available light. She’d come down from the high ridges, drawn by the smell of running water and the anomalous green. She paused at the mound of fresh earth, her foot nudged the corner of the notebook. She knelt, picking it up with hands dirtier and more calloused than her age suggested.

She turned the stiff, warped pages, finding nothing but blank space until she reached the final sheet. There, isolated on the brittle paper, was the single, charcoal drawing: the simple, absolute lines of a dog.

The girl touched the picture with a tentative finger, tracing the familiar shape of the muzzle and the line of the focused gaze. She didn’t know what she was looking at—not a dog, but a diagram of survival. And in the silence of her mind, a new, primal thought formed. It was not a voice, not a memory, but an idea, sharp and clean: Move.

She rose, the notebook tucked into her rags. She walked toward the heart of the valley, a deeper fold in the earth where a stream rushed, hidden by dense undergrowth. It was green, but not a sanctuary. It was just a place to be, a functional location where the maths of survival tipped momentarily in favour of life.

She stopped, her small body tensing. She felt the shift in the air, the subtle alteration of the silence she had learned to trust. She didn't turn around. She spoke, the sound of her own voice rusty and unused in the open air.

"Who’s there?" The only response was the steady sound of the stream. "I have nothing," she said, speaking the language of the Ash, the absolute truth of the road. "No food. No water to spare." A moment passed. Then, a low, guttural noise emerged from the trees—a sound that was not quite a growl, but a question. The girl took a deep breath, clutching the notebook against her chest. "I have this. It tells you to move. That’s all."

Behind her, emerging silently from the shadows of the trees and stepping onto the moss, a dog followed. It was large, a mix of breeds honed to sharp angles by starvation and instinct, its fur the colour of wet ashes. It was low to the ground, watchful, its movements fluid and utterly silent, a perfect extension of the shadows. Its gaze was fixed entirely on the girl, not with aggression, but with intense, focused appraisal. It was calculating her steps, her pace, her vulnerability. The girl slowly turned, confirming the presence she had already sensed. She met the dog’s eyes—eyes that held a familiar, cold intelligence, a reflection of the same ruthless maths that had guided her all her life.

"You’re alone, too," the girl stated, a simple fact. "I saw your picture. In the book." The dog took one, slow step forward. The girl didn't move. She opened the notebook again to the charcoal sketch and held it out, showing the dog the crude image of itself. "They drew you. Said you were the only truth." The dog stopped, its nose twitching. It smelled the ash and sweat on the paper, but beneath that, the metallic tang of old oil, and the fainter scent of something deeper, something familiar and indelible. It recognised the shape, the posture, the absolute command. A new thought, a fresh, cold idea, dropped into the girl's mind. It was a precise instruction, not a demand, the clarity shocking her: Water. Stream is safe. Drink low. You are exposed. The girl gasped, stumbling back half a step. The shock was physical, a jolt that bypassed her ears and settled in her bones. She looked at the dog, whose expression had not changed, the eyes still pools of silent calculation.

"You... you did that?" the girl stammered, her voice a frantic squeak. "You talked?"

I did not talk. Sound is risk. Idea is clean. The thought was a relentless, cold pressure, demanding compliance. Do not waste time on the noise of thought. Move.

The girl felt the instinctive urge to question, to speak, to debate the sudden, internal voice. She wanted to ask how, and why. But the message was too clean, too useful. It aligned perfectly with the brutal logic she understood.

"Alright," the girl whispered, nodding once. She re-folded the notebook and tucked it away. "Water first. Then... where?"

The dog took another slow step forward, its head lowering slightly. South. Up-slope. The scent is stronger there.

"Scent of what?"

Green. The source. The promise. The telepathic thought held a fraction of a dead man’s desperation, a residual fragment of the old loyalty. The lie that keeps us moving.

The girl didn't question the terminology. She understood the concept of a necessary lie. She turned and walked toward the stream, keeping her body low. The dog followed, a shadow stitched to her heels, not out of affection, but out of a shared, absolute calculation.

The only language that mattered was the one that said: live. The girl moved. The dog watched. The shadow of the rose had found a new vessel, and the maths of survival had found a new, lethal partnership. The crossing was complete, but the long walk was just beginning.

Some people move through the world making noise. Thirteen-year-old Leo has learnt to be still. But when an old illustrated book vanishes from the bookshelf, Leo discovers something extraordinary living in the walls of the Victorian house: the Snibbit, a small magical creature that collects beautiful things and understands that silence can be full of meaning. Through carefully preserved fragments from the past, the Snibbit teaches Leo how to navigate a world that isn't built for quiet people.