The Boy On The Bridge

I.

The estuary path became mine by accident. After they let me come back—retake the year, start again—I needed a route home that didn't pass the bus stop where voices still lived in my head. The footbridge was longer, colder, but it belonged to no one. Just gulls and the smell of salt mud and the hiss of reeds when the wind came in from the east.

I walked it every day. Same time. Same rhythm. The repetition was a kind of armour.

The tide was high the day I came back to school. Water lapping at the bridge supports, dark and opaque. I'd stood there for twenty minutes, watching it, before I could make myself walk across. By the second week, I timed my walk for low tide. Safer somehow, seeing the mud beneath. Solid ground, even if I couldn't reach it.

I started noticing things. A heron that fished in the same spot most afternoons, slate-grey and patient. The way the light changed as autumn deepened, turning the water bronze in the late afternoon. The oystercatchers, their orange beaks bright against the mud, piping their strange calls that sounded almost electronic.

Other people used the bridge too. Dog walkers mostly, nodding as they passed. I never nodded back. Kept my eyes down, counted the planks. One hundred and forty-seven from one side to the other. I knew because I'd counted them every day for six weeks.

It was October when I saw him.

II.

He stood near the centre of the bridge, hands on the railing, looking down at the water. The tide was out, just ribbons of brown channel winding through the flats. His school bag sat beside him, unopened. I recognised the jacket first. Then the posture. Then the shape of his head.

Daniel Keppler.

My feet slowed but didn't stop. I kept walking, eyes forward, heartbeat climbing. The bridge was narrow. I would have to pass him.

Ten feet away, he looked up.

Our eyes met.

It lasted three seconds. Maybe four. Long enough for me to notice his breathing, shallow and deliberate. Long enough to smell the estuary salt between us, sharp and mineral. There was no recognition in his face. Or maybe there was, something beneath the blankness, some flicker I couldn't name. His expression wasn't hostile. It wasn't apologetic. It was past both, like faces go when they stop meaning anything at all.

I looked away first. Kept walking. The planks creaked under my boots. The wind pulled at my coat. When I reached the other side, I didn't look back.

But I felt it. That moment. Suspended. Like something I'd have to develop later, when I could breathe again.

That evening, I tried to tell my aunt.

She was chopping vegetables for dinner, the knife making its steady rhythm against the board. I stood in the doorway, the words right there in my throat.

"I saw..."

She looked up, waiting.

Nothing. My throat closed. The words dissolved.

"You alright, love?" she asked.

I nodded. Went upstairs.

III.

My aunt was making tea when I got home the next day. She worked at the sixth-form college, admin mostly. Knew everyone's business without trying.

"Did you know Daniel Keppler?" she asked, not looking up from the kettle.

The name landed like a stone.

"Why?"

She poured the water, slow and careful. "They found him this morning. Down by the estuary." She paused. "It was suicide."

The kitchen went very quiet. The fridge hummed. Outside, a car door slammed.

"Oh," I said.

She set the mug in front of me. Her hand touched my shoulder, briefly, then withdrew.

I drank the tea. It was too hot. I didn't say anything else.

Later that week, she mentioned the funeral had happened. Thursday afternoon. She said it the same way she'd say the bins needed taking out, factual and plain. I realised I hadn't even thought about going. Hadn't considered it. The idea of being in a room full of people, his people, mourning him.

I'd been on the bridge instead. Same time as always. Low tide. The heron in its usual spot.

IV.

That night, I couldn't sleep. I kept seeing his face. Not the face from the bridge, the one from before. Year ten. The corridor outside the music room.

It was January. Cold enough that the heating pipes clanked and hissed. The floor had just been mopped, smelled like cheap lemon cleaner. I was carrying my bag and a folder of sheet music, walking quickly because I was late.

Daniel was there with two others. I didn't remember their names anymore. He wasn't the one who kicked my bag. Wasn't the one who scattered the music sheets across the wet floor. He just stood there, watching. And when I knelt to pick them up, ink already bleeding on the damp paper, he smiled.

Not cruel. Almost bored. Like I was part of the weather.

But there had been another time. Earlier that year, maybe September. I'd seen him alone in the library, sitting at one of the back tables. His head was down, shoulders curved inward. Someone walked past and he looked up, and for a second his face was so raw, so exposed, I'd almost said something. Almost asked if he was alright.

Then someone called his name. He stood up, put the mask back on, and walked away.

I'd forgotten about that. Or buried it. But now it came back, sharp and insistent.

On the bridge, there had been something else. Something I didn't understand.

I got up, turned on the desk lamp, found my sketchbook.

I drew the bridge first. Then the railing. Then the shape of him, looking down. My hand moved without thinking. The pencil scratched against the paper, too loud in the quiet room. I smudged a line with my thumb, trying to capture the angle of his shoulders. I didn't try to make it accurate, just true to the feeling. The suspension, the silence, the space between us.

My hand started to cramp but I kept going.

When I finished, I stared at it for a long time.

Then I drew another. This time, the water. The channels winding through the mud. The way light caught on the surface like scattered glass. I pressed too hard and the pencil point snapped. I got another one.

And another sketch. His hands on the railing. The exact curve of his fingers. The way his school bag sat beside him, slumped like something defeated.

I drew until my wrist ached and my eyes burned. Until my aunt knocked softly on the door at two in the morning and asked if I was alright.

I said yes. She left a glass of water on the desk. Said nothing about the scattered drawings.

When she closed the door, I looked at what I'd made. Eight sketches. Nine. I gathered them up, stacked them carefully, slid them under my mattress.

All except one.

V.

The next day, I went back to the bridge.

It was raining. Fine, cold, persistent. The kind that soaks through everything. The tide was coming in, slow and patient, filling the channels one by one. I stood where he'd stood, looked down at the water. It was dark, stippled with rain. I couldn't see the bottom.

I took out the first sketch, the one of him on the bridge, and unfolded it carefully. The paper was already damp. The lines blurring slightly at the edges.

I tucked it between the railing slats where the wood met the metal post. My fingers were numb, clumsy. It took three tries. The wind tugged at it, but it held.

I didn't know why I did it. It wasn't forgiveness. It wasn't accusation. It was something else. A way of saying: I saw you. I don't know what you saw. But I was there.

The tide kept rising.

I stayed on the bridge until my coat was soaked through. Until a dog walker asked if I was alright and I nodded without speaking and they walked on, glancing back once, uncertain.

The rain got harder. I watched the sketch darken, the paper beginning to curl. When I finally left, it was still there, pinned between wood and metal like something caught between worlds.

VI.

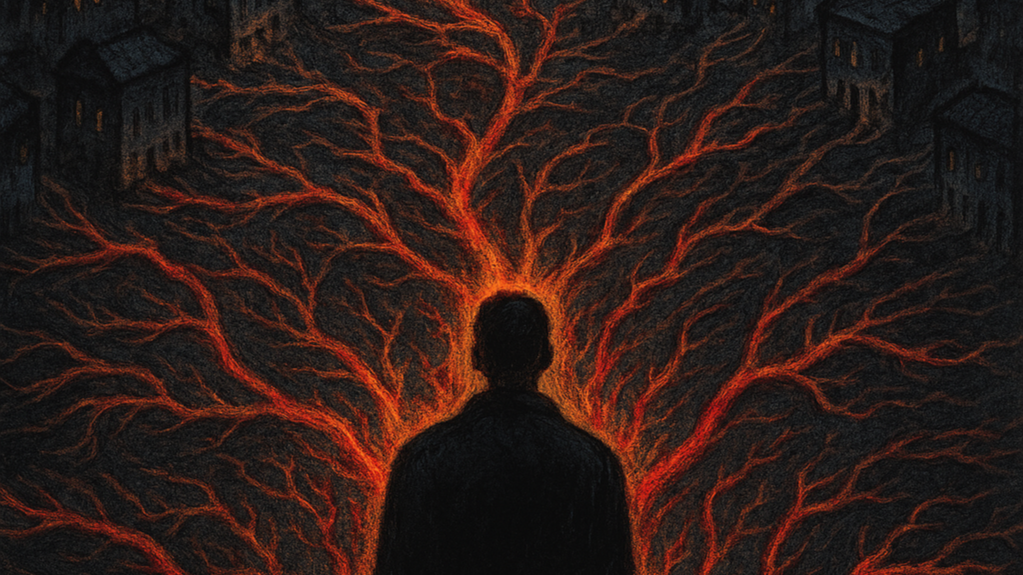

In the days that followed, I began to imagine things I couldn't know.

One image kept returning. Daniel in his bedroom, late afternoon. His hand on the doorknob, hesitating. The carpet beneath his feet, rough and threadbare near the door from years of pacing. Music playing, something with heavy bass that made the walls hum. But he wasn't listening. He was looking at the window, at the grey sky beyond it, at nothing.

I could see it so clearly. The exact angle of light through the curtains, thin and grey. The way his shoulders curved inward. The stillness of his hand on that doorknob, as if he'd forgotten why he'd reached for it. A poster on the wall behind him, something about football, the corners curling away from the blu-tack. A mug on the desk, cold tea with a film forming on top.

And another scene. Earlier that same day, maybe. Daniel on the bridge before I arrived. He drops something into the water. A stone, maybe. Or a coin. Watches it fall. Watches where it disappears. His face is wet but I can't tell if it's rain or tears or spray from the estuary wind. He stands there for a long time. Testing something. Measuring something. Making some calculation I'll never understand.

Then he hears footsteps. Mine. He straightens slightly. Puts his hands on the railing. Looks down. Waits.

But I was making this up. I was writing him a story he might never have lived. Maybe his room was cheerful, painted bright colours, full of photographs and trophies. Maybe he'd never hesitated at a doorknob in his life. Maybe on the bridge he was thinking about dinner, or a girl, or a film he wanted to see.

Or maybe he was drowning long before he reached the water.

I would never know. And the not-knowing was a weight I'd have to carry.

VII.

But something was shifting.

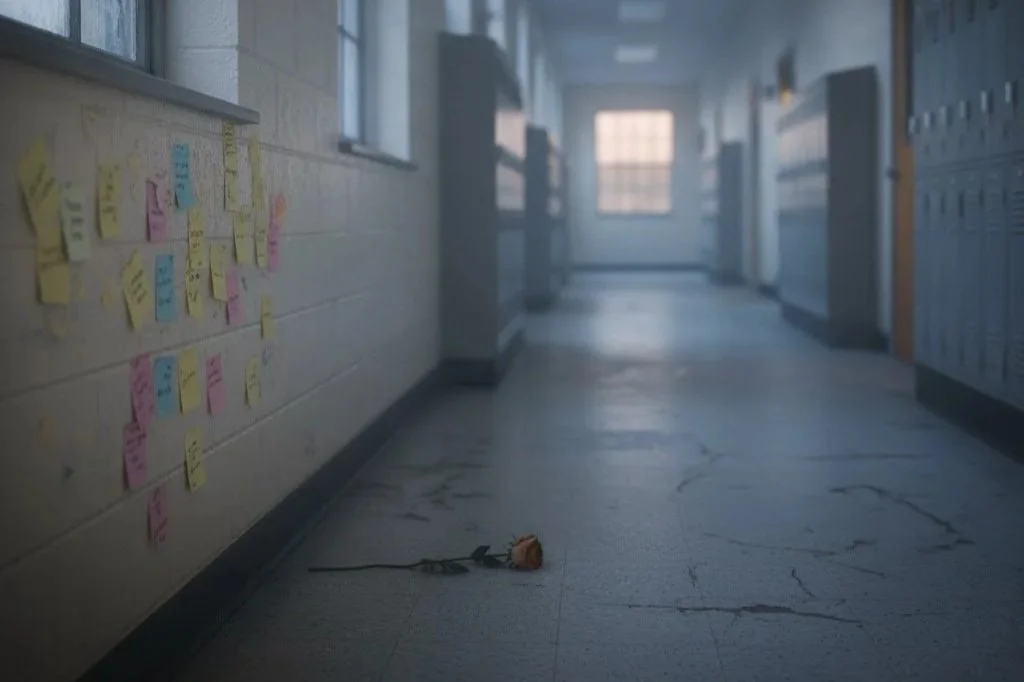

The flashbacks came less often now. When I passed someone in the hallway, I didn't flinch. When I heard laughter, I didn't assume it was aimed at me.

In November, I got an essay back. History. I'd written about the Industrial Revolution, the rise of the working class, typed it up at two in the morning in a fugue state of concentration. B+. Good analysis. Could develop the argument further.

I stared at it for five minutes. I was still capable of this. Still capable of thinking, writing, producing something that made sense to someone else.

One morning, someone held a door open for me. A girl from my English class, dark curly hair, always sat in the front row.

I tried to say thank you. My throat closed. No sound came out. I nodded instead, face burning, and hurried past.

She said, "No worries," to my back.

That night I lay in bed furious with myself. One word. Two syllables. Thank you. Impossible.

The next week, I tried again. Someone passed me a handout in class.

"Thanks," I managed. Just the one word, quiet and rough.

The boy who'd passed it barely glanced up. "Yeah, no problem."

It felt strange. Like learning a language I used to know.

After that, it came easier. A few words here and there. "Yeah." "See you." Small things. But they mattered.

By December, I'd started sitting in the common room sometimes. Not talking. Just sitting with a book, being in the same space as other people. Someone asked if they could borrow a pen. I said yes and handed it over. They said thanks. I said you're welcome.

Two words. A whole conversation.

The bridge became different too. One afternoon, a jogger nodded at me as he passed, breathless and red-faced. I nodded back before I could think about it.

The heron was gone. Migrated maybe, or moved to a better fishing spot. But the oystercatchers were still there, stabbing at the mud with their bright beaks.

The first frost came in late December. The railings were white with it in the mornings, glittering in the weak sun. I stopped wearing gloves so I could feel the cold metal against my palms when I gripped the railing. A way of knowing I was present. Real. Here.

VIII.

One afternoon in January, I went back to the bridge with my sketchbook.

The folded drawing was long gone. I'd known it would be. Taken by the wind or the rain or someone passing by. I didn't replace it.

Instead, I sat on the bench at the far end and drew the estuary. The way the light moved across the water. The distant line of the coast. The birds circling, small and sharp against the winter sky. A dog, far out on the mudflats, black against the grey.

I drew for an hour. Maybe more.

A woman walking her spaniel stopped and watched for a moment. "That's lovely," she said.

"Thanks," I said.

She smiled and walked on.

When I left, the tide was going out again. Footprints in the mud, already dissolving. The water pulling back to reveal the secret geography beneath. Channels and rivulets, stones and shells, all the hidden structure that the high tide concealed.

I walked home slowly. My aunt was making dinner when I arrived, the kitchen warm and bright.

"Good day?" she asked.

"Yeah," I said. "Not bad."

She glanced at my sketchbook, said nothing, turned back to the stove. But I saw her smile, just slightly.

That night, I looked at the other sketches. The ones I'd kept. I spread them out on my desk, studied them in sequence. The bridge. The water. His hands. His posture. The space between us.

I didn't hide them anymore. I left them there, pinned to the wall above my desk with blu-tack. Not a shrine. Just a record. Something that happened. Something I witnessed.

IX.

There's a moment I keep returning to.

Two people on a bridge. One walking. One still. Eye contact, brief and inexplicable, the smell of salt between them. Then nothing. Just the sound of footsteps fading, the hiss of wind through reeds, the slow clockwork of the tide.

I don't know what he saw when he looked at me. I don't know if he remembered who I was. I don't know if our paths crossing that day meant anything, or if it was just coincidence, two people passing on a bridge, each carrying something too heavy to name.

But I know this: I was there. I saw him. And whatever he was carrying, he set it down in the water that night, and it didn't wash back.

Months later, I still walk the footbridge. The estuary is tidal, rhythmic, reliable. The water rises and falls.

I sketch less often now. But sometimes, on quiet afternoons, I'll stop in the middle of the bridge and look down at the channels winding through the mud. And I'll think of him. Not the boy who hurt me. Not the boy who died. Just the boy in between, standing on a bridge, staring at water, seeing something I'll never see.

A new heron has arrived. Smaller than the first. It stands in the shal

lows at low tide, waiting with infinite patience for something to move beneath the surface.

The reeds bend and recover.

Author's Note

This story is based on a real encounter.

25 years ago, I crossed paths with someone who had bullied me. It was brief, just a moment, with eye contact, but nothing was said. Hours later, I learned he'd taken his life.

I've changed almost everything. The setting, the names, the circumstances before and after, the specific details of our shared history. The estuary, the bridge, the sketching, the aunt: these are all invented. But the core remains true: that suspended moment of recognition, the weight of not knowing what passed between us, the years spent trying to understand what I witnessed.

I don't know what he was thinking. I don't know if seeing me mattered, or if I was just another face in his final hours. I don't know if he remembered who I was, or what he'd done. I'll never know.

What I do know is that trauma is complicated. That people contain multitudes. That cruelty and suffering can exist in the same person, sometimes at the same time. That recovery isn't linear, and neither is grief, especially grief for someone who hurt you.

This story isn't about blame. It's not about forgiveness either. It's about being a witness to something unknowable, and learning to live with that weight.

If you're struggling, please reach out. Some people want to help.

UK Resources:

Samaritans: 116 123 (24/7)

PAPYRUS (for under 35s): 0800 068 4141

Shout Crisis Text Line: Text SHOUT to 85258

Some people move through the world making noise. Thirteen-year-old Leo has learnt to be still. But when an old illustrated book vanishes from the bookshelf, Leo discovers something extraordinary living in the walls of the Victorian house: the Snibbit, a small magical creature that collects beautiful things and understands that silence can be full of meaning. Through carefully preserved fragments from the past, the Snibbit teaches Leo how to navigate a world that isn't built for quiet people.