The Playground Trial

The drama room was a place of raw, inescapable feelings. It smelled of a dense, sour clot of sweat sealed into the carpet, a smell that felt like trapped regret, and the chemical tang of dry-erase markers. The sound of the ancient CD player; that wheezing, searching whir. That wasn’t ambiance; it was static in my head, perfectly mirroring the noise Adam caused inside me.

Adam sat on the stage’s edge, hoodie pulled high. He had that look; half-smirk, half-contemptuous glaze. The same look that felt like a physical violation. I remember the texture of my hatred for him: sharp, clean, and surgical. It wasn't just anger; it was the chilling, constant urge to erase him. I replayed his cornering me in the cloakroom, tearing my sketchbook page by page, as if he were peeling the skin from my own ribs.

We had to act in The Playground Trial, a nauseating irony. He was the quiet victim; I, the theatrical bully. Miss Penrose called it “subversive.” To me, it was just the inevitable, irrevocable act of our shared poison. Adam read his lines like they were utterly beneath him, but when he stood on the stage, he filled the space like smoke, like something that always stains.

“You think you’re better than me just ’cause you read books?” I said, the venom in my voice real, not scripted.

He met my gaze, his eyes flat and unnerving.

“I just want to be safe,” he delivered.

Safe. That word was a lie in his mouth. He didn't want safety; he wanted silence. He wanted me small.

I stepped closer, the cold, unexpected weight of the prop knife up my sleeve pressing against my arm. I remember Miss Penrose saying it was "weighted for realism." It felt weighted with consequence. This was the final scene.

“You ruined everything,” I shouted, as the line cracked.

“I just wanted to be safe,” he repeated, quiet but hard.

I raised the knife. His chest rose, then fell. I was holding my breath, fighting the sudden, dizzying panic that wanted me to drop the blade and run, instead I lunged.

The blade met cloth. He dropped fast, too fast. There was a sound; soft, wrong. Not fabric ripping, not quite.

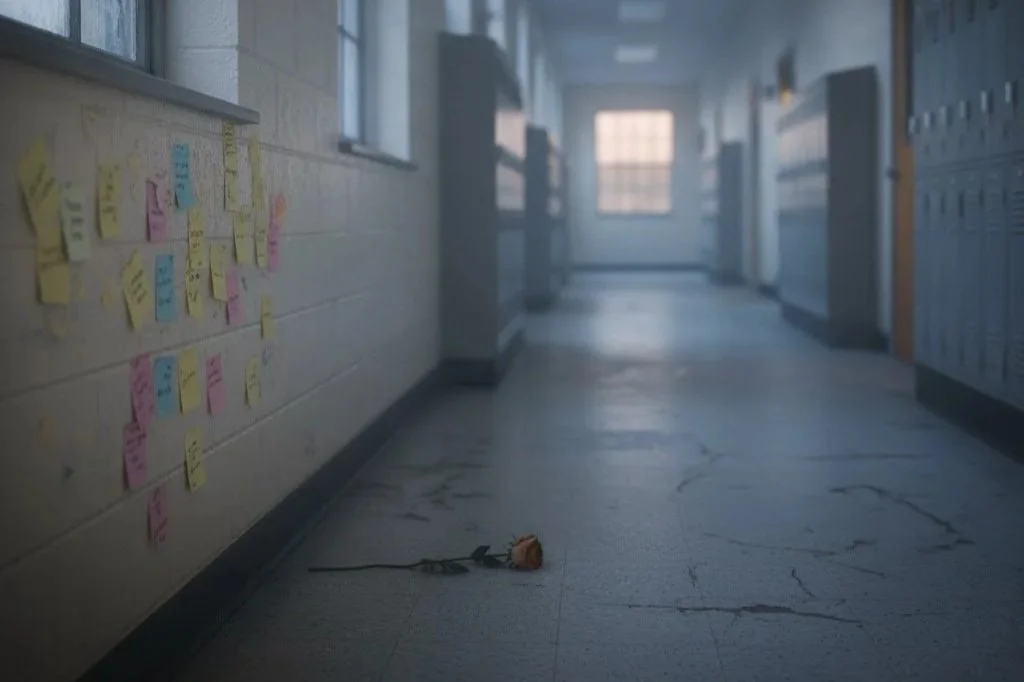

Everything paused. Then the noise came back, overwhelming. Shouts. Cheers. Then the sharp, breaking voices. I stood frozen, the knife dangling from my fingers like a final verdict. The stage lights began to die; not all at once, but in jagged pieces. The room dimmed like dusk falling over a deserted playground. My vision narrowed, like someone were drawing curtains inside my head. I couldn’t tell if I was falling out of the moment or deeper into it.

Then the lights went out. The ceiling was a blur; a square of plaster, soft in the half-light. Except for a soft, constant hum, the room was silent. I lay still. The stiff covers pressed against me. My hand ached, a deep, bone-weary throb. I didn't remember falling asleep.

The knife wasn’t there, of course it wasn’t, but I could still feel its weight. Not in my palm, somewhere deeper, a mark under the skin.

Adam’s face hovered behind my eyes, not bleeding, just smirking as always.

The small digital clock on the low bedside table read 3:17. Cold. Lifeless.

The window was high on the wall, shrouded by a heavy, pale curtain that offered no view, only a diffused, uncertain light; just enough to read the dust motes spinning in the air. Somewhere in the structure, a pipe groaned, the kind of sound that could be anything; a footstep, a breath, a memory shifting its weight.

I thought about the stage lights. How they’d dimmed. How the edges of the room had curled inward like the play was ending. Or like I was waking up. I didn’t know which. I closed my eyes, the stage was still there, and so were Adam and the knife. And I was still in this room.

Some people move through the world making noise. Thirteen-year-old Leo has learnt to be still. But when an old illustrated book vanishes from the bookshelf, Leo discovers something extraordinary living in the walls of the Victorian house: the Snibbit, a small magical creature that collects beautiful things and understands that silence can be full of meaning. Through carefully preserved fragments from the past, the Snibbit teaches Leo how to navigate a world that isn't built for quiet people.