Sweetners

# Sweeteners

Sara ran. Her lungs clawed for air, her chest throbbed, and her legs burned with every step. She hated being tall, hated the way her knees jutted out in photographs, the way teachers asked her to reach things, the way she couldn't simply disappear. Her phone died just as she stumbled down an unfamiliar street. She was certain she had charged it. The houses looked wrong; too far apart, too quiet. Panic bloomed in her chest.

She collapsed outside a crooked house with a broken garden wall. A voice called out.

"You all right, dear?" An old woman, perhaps ninety, peered over the wall. Her hair was silver and coiled like smoke.

"I'm lost," Sara said, breathless. "My phone's dead."

The woman nodded. "Come in. Use mine. I'll make coffee."

Inside, the hallway was narrow, lined with sepia photographs of children who didn't smile. Sara dialled her mum's number and left a shaky message.

"I'm okay. Just... I hate being tall."

The woman returned with two steaming mugs.

"Sweeteners," she said, dropping a small white pill into Sara's cup from a tin box. "Helps with bitterness."

Sara sipped. The warmth settled her.

"I was running because they wouldn't stop," Sara said. "Gareth Jones... He called me 'beanpole' again. They chanted it like it was a spell. Like it could shrink me."

The woman took a sip of her coffee.

"I hate it," Sara whispered. "I hate being tall. I hate how I can't hide. I just want to be... smaller. Invisible."

The woman's gaze didn't waver. "You're tired of being seen."

She leaned forwards, her voice low and steady. "Let me tell you a story whilst we wait. About a boy named Midge."

---

Henry Joseph Malcolm MacDonald, known to everyone as Midge, was short. Not just short. A foot shorter than the boys, two feet shorter than the girls. He hated his height with a quiet, burning intensity. He was the punchline, the nickname, the reason people always picked him last.

He tried everything. Stretching exercises, hanging from monkey bars, drinking milk at midnight. One day, he stole his father's weights, climbed the only tree in the neighbourhood (a crooked old thing) and jumped, looping the rope around his legs. He hung there overnight like a forgotten ornament. His father found him at dawn and grounded him, not for the danger, but for the embarrassment.

Midge gave up. He folded himself inwards. Until he met her.

Her voice had the quality of rain-soaked sound, and her eyes were like wet leaves. She stood in the hedge clearing behind the school.

"You're unhappy," she said. "I can help."

She showed him a pill: small, white, from a tin that looked older than the school itself.

"Take it with coffee before bed," she said. "But don't go to bed. Go outside. Sleep standing up. You'll grow taller than you ever imagined."

Midge didn't believe her, but she met him every day. After two months of relentless mockery from his classmates, he'd had enough.

That night, he brewed coffee, dropped in the pill, and drank it. The taste was bitter, metallic. He crept outside and stood in the garden, eyes closed, heart thudding.

At midnight, pain stabbed through him.

His limbs stiffened. His skin turned brown and rough. His throat became thick bark. Roots burst from his shoes, curling into the soil. He was immobile. He was becoming a tree.

He tried to move. His arms creaked.

His mother noticed the new tree the next morning. "Was that always there?" she asked. His father shrugged.

They realised Midge was gone. They searched the house. Called the school. Filed a report. But the tree remained. It stood tall, bark dark, leaves trembling in the wind as if they knew something.

Time moved on. Eventually Midge was all but forgotten. He grew. Taller than any boy in his class. Taller than the school. He felt everything: rain, laughter, grief. Children built treehouses in his branches and carved initials into his bark. He bore their secrets like tattoos.

Years passed. One day, the woman returned and found him gone. Someone had chipped the tree away for a new school playground. She stood in the clearing, holding the tin. She said, "You should have grown, not vanished."

But Midge hadn't vanished.

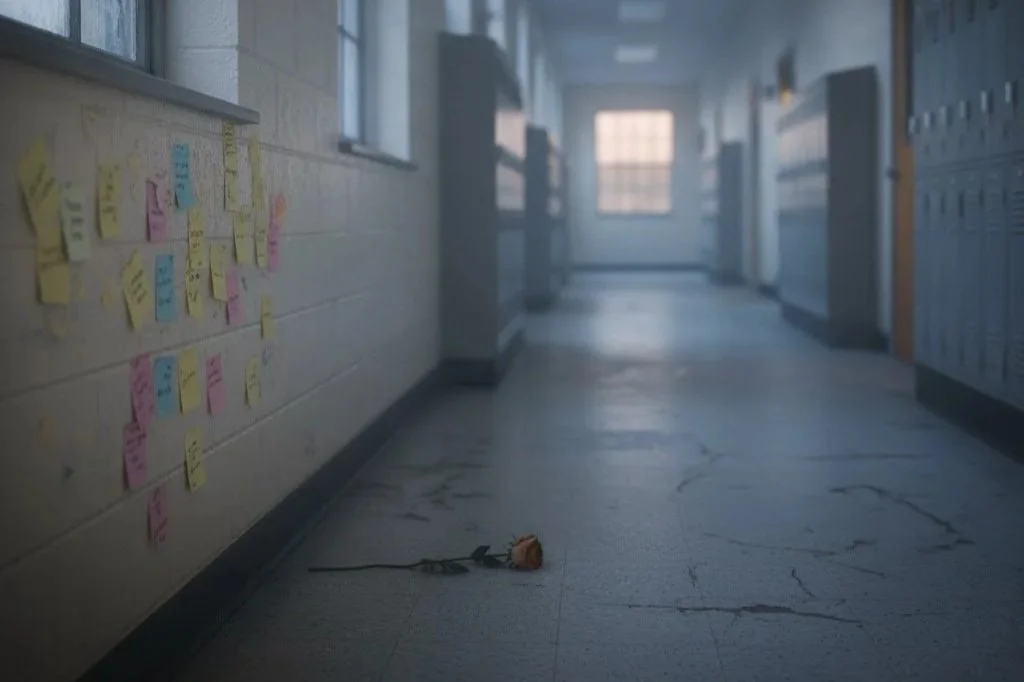

At the new school, there was a mural. A tree, painted in soft greens and browns, its branches stretching across the wall. It had appeared overnight. The principal wanted it removed, but the students protested. They said it felt right.

In the mural, the tree had eyes like wet leaves. And sometimes, the branches seemed to whisper.

Midge had grown. He had become a story. A memory. A myth that refused to be erased.

---

The woman leaned back in her chair, placing her cup on the side table.

"It's wrong to get preoccupied with the way you look," she said.

Sara finished her coffee. Her chest felt warm. Her legs no longer ached. Her hands seemed thinner, paler, almost translucent in the lamplight.

There was a knock at the door.

The old woman stood slowly, smoothing her cardigan, and opened it with the latch still on.

"I'm looking for my daughter," said the woman outside. Sara's mother. "She's tall. Brown hair. She called from this number."

"No girls here," the old woman replied. "Haven't seen anyone."

Sara's mother squirmed with anxiety. "She wouldn't just vanish."

She shifted her handbag higher on her shoulder, brushing her fringe back. Her fingers lingered on her temples, tracing the edge where the bright blonde dye met the pale grey regrowth she'd been desperately trying to hide. She hated how quickly the grey seemed to reappear, mocking her attempts to hold onto youth.

The old woman smiled. "Come in. Use the phone. I'll make coffee."

Inside, Sara's mother stepped carefully. She dialled her daughter's number and left a message.

A small, white-bodied spider, with legs too long for its size, crawled across the table. Sara's mother hated spiders more than any other creatures. It skittered across a phone charger cable, coiled loosely on the table like a forgotten lifeline.

Sara's mother crushed it without thinking.

The old woman returned, carrying two mugs. "Sweeteners," she said, dropping a pill into the coffee. Her eyes flicked to the smear. A subtle collapse crossed her face.

"Thank you." Sara's mother said, taking the mug from the tray. "You're very kind."

She took a sip, then placed it on a corner table next to an empty mug. She noticed a familiar phone: Sara's phone, now subtly glowing with a sliver of charge.

Suspicions rising, Sara's mother made her excuses. "I think I'll try calling my husband. Perhaps he's heard from her." She picked up her daughter's phone and walked to the back of the hallway, where the old-fashioned rotary phone sat, and began to dial her daughter's now-powered number.

Before she could finish, the phone in her hand vibrated. A silent, internal ring that made the glass rattle faintly. Sara's mother stared at the screen, which showed a single, blank incoming call.

She answered it.

Silence.

Then a faint sound; a soft clicking, like tiny legs tapping glass, came from the phone's earpiece. Then a whisper, barely audible: "I'm here."

The line went dead, and the phone's screen immediately went dark again.

"She was unhappy," the woman said quietly, shuffling into the hall. "She wanted to be smaller, to disappear."

"What did you do?" Sara's mother asked.

"I offered her quiet. She drank it."

Sara's mother backed away.

"She was brave," the old woman said softly as the mother reached the threshold. "She chose transformation."

Sara's mother didn't reply.

---

Sara's mother stepped into the night, heels clicking against the pavement, her shadow stretching long behind her. She made it home.

Her husband, arriving half an hour later, found the house empty, the porch light on, and the front door unlocked. He called her name. He checked the messages she'd left on his office line: a frantic, choked description of a crooked house, a strange old woman, and a missing daughter.

He searched the house, finding only a half-empty mug of cooling coffee sitting on the kitchen counter. He called the police, then paced the floor until dawn.

At sunrise, he finally noticed a small, utterly mundane object lying on the master bathroom counter. A wooden-backed hairbrush. It wasn't one he recognised. It was clean, too clean. Every single one of its bristles was worn to a sharp, brittle point, and across the cushion, a faint blonde coating, the colour of the dye his wife used to fight her grey hair.

---

The old woman sat down. She looked at the empty mugs. She looked at the place where the spider had been.

"It's wrong," she whispered, "to get preoccupied with the way you look."

Then she reached for the tin.

And waited.

Some people move through the world making noise. Thirteen-year-old Leo has learnt to be still. But when an old illustrated book vanishes from the bookshelf, Leo discovers something extraordinary living in the walls of the Victorian house: the Snibbit, a small magical creature that collects beautiful things and understands that silence can be full of meaning. Through carefully preserved fragments from the past, the Snibbit teaches Leo how to navigate a world that isn't built for quiet people.